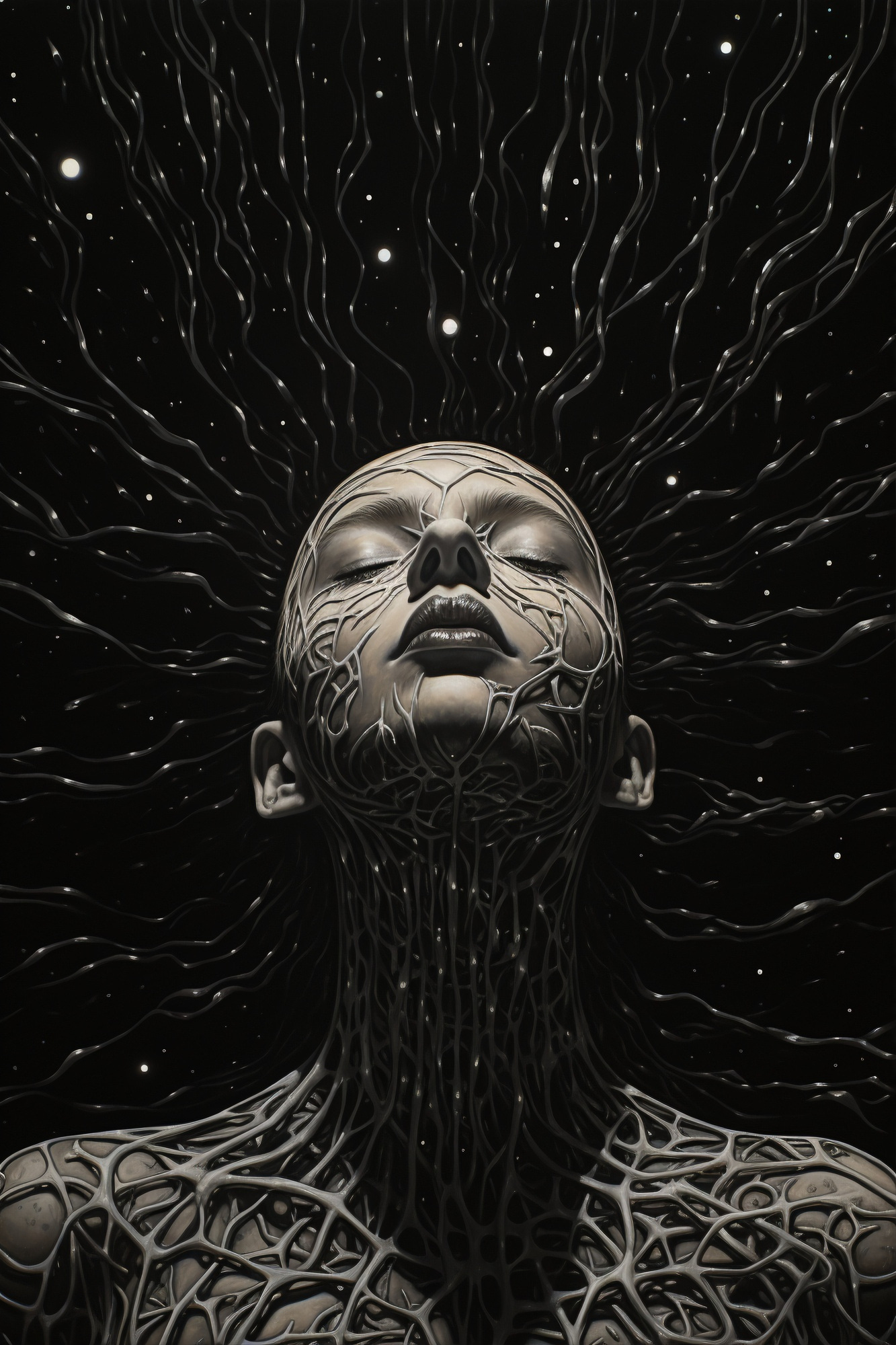

Beyond the Five

A Revolutionary Map of Human Sensory Architecture

For centuries, we’ve been taught a fundamental lie about human perception: that we possess exactly five senses. This reductive framework—inherited from Aristotle and calcified through institutional repetition—has constrained our understanding of consciousness itself. The truth is far more extraordinary. Human beings operate with a minimum of twenty distinct sensory channels, each with its own neural architecture, phenomenological quality, and evolutionary purpose. This series represents a comprehensive exploration of human sensory architecture as it actually exists—not as simplified educational mythology, but as the sophisticated, multi-dimensional perception system that enables us to navigate physical reality, emotional landscapes, temporal dimensions, and energetic fields simultaneously. Over the next five articles, we’ll examine each sense in depth, reclaiming the full bandwidth of human perception that culture has systematically suppressed. Welcome to the revolution.

This is part one of a six-part series. Please check back each week for new installments.

INTRODUCTION: THE SENSORY MYTHOLOGY WE INHERITED

For centuries, Western education has perpetuated a fundamental lie about human perception: that we possess exactly five senses. Sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. This reductive framework, inherited from Aristotle and calcified through institutional repetition, has constrained our understanding of consciousness itself.

The truth is far more extraordinary.

Human beings operate with a minimum of twenty distinct sensory channels, each with its own neural architecture, phenomenological quality, and evolutionary purpose. We are not five-sense creatures stumbling through a complex world. We are twenty-sense beings capable of perceiving dimensions of reality that our cultural frameworks have systematically ignored, dismissed, or pathologized.

This article represents a comprehensive exploration of human sensory architecture as it actually exists—not as simplified educational mythology, but as the sophisticated, multi-dimensional perception system that enables us to navigate physical reality, emotional landscapes, temporal dimensions, and energetic fields simultaneously.

We will examine each of the twenty senses in depth, exploring their:

Neurological basis (the hardware)

Phenomenological quality (what it feels like to perceive through this sense)

Evolutionary function (why we developed this capacity)

Cultural recognition or suppression (how different traditions acknowledge or deny this sense)

Practical applications (how conscious engagement with this sense enhances life)

Pathologies and distortions (what happens when this sense malfunctions)

This is not metaphysics. This is not pseudoscience. This is a rigorous examination of documented human capacities that have been marginalized by a culture that values only what it can easily measure and commodify.

By the end of this exploration, you will possess a fundamentally altered understanding of what it means to be a sensing human being. You will recognize capacities you have been using unconsciously your entire life. And you will understand why reclaiming the full bandwidth of human perception is not just personally transformative—it is culturally essential.

Let us begin.

PART ONE: THE FOUNDATIONAL FIVE

SENSE 1: SIGHT (Vision / Photoreception)

Neurological Basis: Vision is mediated primarily through the eyes, specifically the retina’s photoreceptor cells: rods (sensitive to light and dark, enabling night vision) and cones (sensitive to color, with three types responsive to different wavelengths). Visual information travels through the optic nerve to the occipital lobe’s visual cortex, where it is processed into coherent images. However, vision is not passive reception—the brain actively constructs visual reality through prediction, filling gaps, and interpreting ambiguous data.

Phenomenological Quality: Vision creates the experience of a spatial field extending outward from the body. It provides information about distance, depth, color, movement, and form. Unlike other senses, vision allows us to perceive objects at great distance without direct contact, creating the illusion of “objective” reality “out there.” This spatial extension contributes to vision’s cultural dominance as the “most reliable” sense.

Evolutionary Function: Vision evolved to enable navigation, predator detection, food identification, and social signaling. Primate vision, particularly, developed enhanced color perception to identify ripe fruit and read subtle facial expressions. The placement of eyes on the front of the face (rather than sides) creates binocular vision, sacrificing peripheral awareness for enhanced depth perception—a predator’s adaptation.

Cultural Recognition: Vision dominates Western epistemology. “Seeing is believing.” “I see what you mean.” “Visionary leadership.” Our language privileges visual metaphors for understanding. The Enlightenment elevated vision as the path to knowledge, while simultaneously devaluing other sensory ways of knowing. In contrast, some Indigenous cultures and contemplative traditions recognize the limitations of vision—its susceptibility to illusion, its tendency to create the subject/object split that fragments wholeness.

Practical Applications: Conscious engagement with vision includes:

Distinguishing between “looking” (passive reception) and “seeing” (active attention)

Developing peripheral awareness (soft focus vs. hard focus)

Recognizing visual illusions and optical biases

Understanding how emotional state colors visual perception

Training visual memory and pattern recognition

Exploring the visionary capacity—inner sight, visualization, imagination

Pathologies: Beyond physical blindness and common refractive errors, vision can malfunction through:

Agnosia (inability to recognize objects despite intact sight)

Prosopagnosia (face blindness)

Visual hallucinations (seeing what isn’t physically present)

Tunnel vision (literal and metaphorical narrowing of perceptual field)

Cultural conditioning (literally not seeing what doesn’t fit our conceptual framework

the “invisible gorilla” phenomenon)

creativecosmosmagazine.online

Advertisement

SENSE 2: HEARING (Audition / Mechanoreception of Sound)

Neurological Basis: Sound is mechanical vibration traveling through air (or other medium). The outer ear captures and funnels these vibrations to the eardrum, which vibrates in resonance. These vibrations transfer through three tiny bones (malleus, incus, stapes) to the cochlea—a fluid-filled, spiral structure lined with hair cells that convert mechanical movement into electrical signals. Different frequencies stimulate different regions of the cochlea, allowing pitch discrimination. Auditory information travels via the auditory nerve to the temporal lobe’s auditory cortex.

Phenomenological Quality: Hearing creates an omnidirectional field of awareness. Unlike vision, which requires facing toward an object, hearing operates 360 degrees. Sound arrives from all directions simultaneously, creating a spherical rather than directional perception field. Hearing also penetrates barriers—we hear through walls, around corners, in darkness. This creates an intimate relationship with sound; it enters the body, vibrates our bones, and cannot be “closed off” the way eyes can close.

Evolutionary Function: Hearing evolved for predator detection (sounds approaching from any direction), communication (vocalizations, language), and environmental awareness (weather changes, water sources, spatial acoustics). Human hearing is particularly sensitive to frequencies of human speech, and infants can discriminate phonemes from all human languages before cultural conditioning narrows this range.

Cultural Recognition: Many spiritual traditions recognize hearing as sacred—the “word” of God, the primordial sound (AUM/OM), the voice of ancestors. “In the beginning was the Word.” Oral cultures privilege auditory knowledge transmission over visual/written forms. However, modern industrial culture has created unprecedented noise pollution, gradually deafening both literal hearing and the capacity for deep listening.

Practical Applications:

Distinguishing between hearing (passive) and listening (active attention)

Developing sensitivity to tonal quality, rhythm, silence

Recognizing how sound affects emotional and physiological state

Training musical ear and perfect pitch capacities

Exploring soundscapes and acoustic ecology

Cultivating the “inner ear”—auditory imagination, memory, and composition

Pathologies:

Deafness (partial or complete loss of auditory capacity)

Tinnitus (phantom ringing or buzzing)

Auditory processing disorder (hearing intact but comprehension impaired)

Hyperacusis (painful sensitivity to normal sound levels)

Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices or sounds not present)

Cultural deafness (inability to hear what contradicts our beliefs—the “selective hearing” phenomenon)

SENSE 3: SMELL (Olfaction / Chemoreception)

Neurological Basis: Smell detects airborne chemical molecules. The olfactory epithelium in the nasal cavity contains millions of olfactory receptor neurons, each tuned to specific molecular shapes. When molecules bind to these receptors, electrical signals travel via the olfactory nerve directly to the olfactory bulb—crucially, this pathway bypasses the thalamus and connects directly to the limbic system (emotional brain) and hippocampus (memory formation). This direct connection explains smell’s powerful link to emotion and memory.

Phenomenological Quality: Smell is intimate, immediate, and involuntary. We cannot “close” our nose the way we close our eyes. Scents arrive unbidden, triggering instant emotional responses and vivid memories. Smell operates below conscious awareness much of the time (we habituate rapidly to constant scents) but can instantly demand attention when detecting danger, desire, or the deeply familiar. Smell is also temporal—scents dissipate, drift, linger, and cannot be easily “held” or “examined” the way visual objects can.

Evolutionary Function: Olfaction evolved for detecting food quality (rotten vs. fresh), identifying kin vs. strangers, sensing predators, finding mates (pheromones and MHC compatibility), and spatial navigation (scent trails, territory markers). Humans are “microsmatic” compared to macrosmatic animals like dogs, but our olfactory capacity remains far more sophisticated than commonly acknowledged.

Cultural Recognition: Western industrial culture has systematically suppressed olfaction, associating body odor with primitiveness and creating an entire industry devoted to scent erasure and replacement. In contrast, aromatherapy traditions, perfumery arts, and some Indigenous cultures maintain sophisticated olfactory knowledge. The Yolngu people of Australia, for instance, use smell as a primary navigational sense.

Practical Applications:

Conscious breathing to enhance olfactory awareness

Scent layering and anchoring (using specific scents to trigger desired mental/emotional states)

Developing discriminatory capacity (identifying subtle notes in complex scents)

Exploring scent memory and nostalgia

Recognizing how smell influences attraction, repulsion, and bonding

Training the “scent imagination”—the ability to recall and mentally construct scents

Pathologies:

Anosmia (complete loss of smell)

Hyposmia (reduced smell capacity)

Dysosmia (distorted smell perception)

Phantosmia (smelling scents not present)

Hyperosmia (heightened, often overwhelming smell sensitivity)

Cultural anosmia (industrially-induced inability to distinguish natural scents)

SENSE 4: TASTE (Gustation / Chemoreception)

Neurological Basis: Taste detects dissolved chemical molecules through taste receptor cells clustered in taste buds, primarily on the tongue but also in the throat and palate. Traditionally, five basic tastes are recognized: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami (savory). Recent research suggests additional taste categories including fat, metallic, and calcium. Taste signals travel via cranial nerves to the gustatory cortex in the insula and frontal operculum.

Phenomenological Quality: Taste is perhaps the most obviously evaluative sense—pleasure and disgust are immediate, visceral responses. Unlike vision or hearing, which can remain relatively neutral, taste instantly categorizes: good/bad, safe/dangerous, nourishing/toxic. What we call “taste” is actually a complex synthesis of gustation, olfaction (smell accounts for ~80% of flavor perception), and trigeminal sensations (texture, temperature, pain—the “burn” of chili or “coolness” of mint).

Evolutionary Function: Taste evolved primarily for food selection. Sweet indicates calories (ripe fruit, honey). Sour signals fermentation or unripe fruit. Salty indicates necessary minerals. Bitter warns of potential toxins (most poisons taste bitter). Umami identifies protein-rich foods. This sense operates as a gatekeeper, determining what enters the body.

Cultural Recognition: Every culture develops sophisticated taste knowledge—cuisine as cultural identity. However, modern industrial food production has hijacked taste perception through supernormal stimuli (hyperpalatable processed foods engineered to overwhelm natural taste preferences). Some contemplative traditions use taste mindfulness as meditation practice.

Practical Applications:

Eating slowly to distinguish true gustation from olfaction and texture

Developing discriminatory palate (wine tasting, tea ceremony, etc.)

Recognizing how emotional state affects taste perception

Understanding taste as communication (the body telling you what it needs)

Exploring taste memory and nostalgia

Cultivating “gustatory imagination”—the ability to recall and mentally construct tastes

Pathologies:

Ageusia (loss of taste)

Hypogeusia (reduced taste sensitivity)

Dysgeusia (distorted taste, often metallic)

Hypergeusia (abnormally heightened taste)

Cultural dysgeusia (preference for artificial flavors over natural foods)

SENSE 5: TOUCH (Tactition / Somatosensation)

Neurological Basis: “Touch” is actually a constellation of distinct mechanical and chemical receptors in the skin, muscles, and joints. These include:

Mechanoreceptors (pressure, vibration, texture)

Thermoreceptors (temperature—explored separately as thermoception)

Nociceptors (pain—explored separately as nociception)

Different receptor types respond to different stimuli (Meissner’s corpuscles for light touch, Pacinian corpuscles for deep pressure and vibration, Ruffini endings for skin stretch, Merkel cells for sustained pressure and texture). Tactile information travels via spinal nerves to the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe.

Phenomenological Quality: Touch is the most intimate sense—it requires contact. Unlike vision or hearing, which operate at a distance, touch collapses the subject/object boundary. Touch is also reciprocal; when you touch something, it simultaneously touches you. This reciprocity creates a unique relational quality. Touch includes both active exploration (haptic perception—actively feeling objects) and passive reception (being touched).

Evolutionary Function: Touch provides information about object properties (texture, hardness, temperature, shape) essential for tool use and manipulation. It also mediates social bonding—grooming, caregiving, sexual intimacy. The skin is the body’s largest organ, and touch deprivation in infancy causes severe developmental impairment, demonstrating that touch is not luxury but necessity.

Cultural Recognition: Different cultures have vastly different “contact norms.” Some cultures are “high-touch” (frequent physical contact in daily interaction), others “low-touch” (physical contact reserved for intimates). Western medical culture increasingly recognizes “therapeutic touch” benefits but remains ambivalent about non-clinical touch. Many spiritual traditions include hands-on healing practices.

Practical Applications:

Distinguishing between different touch qualities (pressure, vibration, texture, temperature)

Developing haptic exploration skills (feeling objects to understand their properties)

Recognizing how touch affects emotional regulation and bonding

Understanding touch as communication (the “language” of hands)

Exploring touch memory (the body’s tactile archive)

Cultivating “tactile imagination”—the ability to recall and mentally construct touch sensations

Pathologies:

Tactile agnosia (inability to identify objects by touch despite intact sensation)

Allodynia (normally non-painful stimuli perceived as painful)

Numbness (loss of tactile sensation)

Hyperesthesia (abnormal increase in sensitivity)

Touch aversion (tactile defensiveness, often trauma-related)

Cultural touch deprivation (isolation from healthy physical contact)

THE FOUNDATION IS ONLY THE BEGINNING

The five senses you were taught in elementary school are real—but they represent less than 25% of your actual sensory bandwidth. Vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch are the senses culture acknowledges because they orient us toward the external world, toward objects we can measure, commodify, and control. But human perception doesn’t stop at the skin.

What you’ve just explored are the senses that point outward. In Part Two, we turn inward—to the five sensory systems that monitor your body’s position, movement, temperature, pain, and internal state. These are the senses you use every moment of every day without conscious awareness. They are the reason you can walk without watching your feet, reach for a glass without calculating distance, or know you’re hungry before your stomach growls.

These internal senses—equilibrioception, proprioception, thermoception, nociception, and interoception—are not supplementary. They are foundational to consciousness itself. Without them, you would be utterly disconnected from the physical vehicle that houses your awareness.

You are about to discover the architecture beneath the architecture.

Next week: Part Two explores the five senses that tell you where your body is, what it’s doing, and what it needs—even when your eyes are closed.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY! For the creative, the sensitive, and the intuitive…